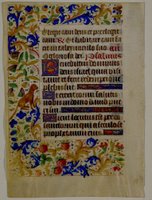

15th-century Book of Hours. Northern France, c.1470-80.

15th-century Book of Hours. Northern France, c.1470-80.www.humi.keio.ac.jp/.../ leaf/main/106-r.html

In this post I ask how perspectives on multimodality might change the way we see writing in textual practices.

Writing and the 'visual turn'

I have a thesis statement for this post and it's this:

Writing continues to be important despite the widely recognised 'visual turn' in textual communication in electronic media. At the same time, definitions of 'writing' are undergoing profound change.

Although it is no doubt true that images abound in textual domains formerly dominated by writing (news media, for example) and new domains (such as the web) have emerged bringing more visual possibilities, to set up an opposition between writing and image, or even to see image as somehow ousting writing in a revolutionary process, would be to miss something important about representation today.

The priviliging of image overlooks not only the continuing social value attached to writing as a semiotic, as a sign-making resource, but also the potential (the 'affordances') of writing itself as both a temporal and spatial, verbal and visual, resource.

Writing, I suggest, has always had these dual properties. It's always been in some way connected to the visual image. Certain periods of textual practice, such as the web today or the medieval book of hours, make this connection - it is more of an intertwining - more visible. At other times it seems more remote, with distinct modes susceptible to schematic notions of grammar, and the feeling that one can talk about 'writing' and 'image' without reference to the practices that use them.

Multimodality includes writing

In one sense, it is obvious that writing - written text - continues to perform major roles in society. Mastery of writing is still seen as central to success in most educational contexts. Indeed, it seems to be more, not less, important in getting access to educational insititutions. Think of the role played in university entrance today by the student personal statement in the UK or the college essay in the US, genres almost exclusively produced in prose writing, and judged as written products.

Then there is the role played by writing in job applications on top of the traditional C.V. Writing is used increasingly in transitional and 'border' situations where power relations are often at their most acute (in immigration and asylum, for example), in administration and bureaucracy, in law and arbitration. Then there is the media, of course. And blogs. And email. Written text in global communications and on the web shows no sign of lessening in quantity, relevance and power.

But writing is far from being a stable mode sustained by a grammar and conventions which are immune from history. Today's writing practices are not yesterday's. Writing changes. In today's world writing comes into closer and more interactive contact with other modes such as image, music and the spoken word. The exclusive aura of its traditional syntax becomes challenged in a multiplicity of ways. It can less and less be used and interpreted as a mode in triumphant isolation from other modes.

New landscapes for writing

In particular, I suggest, it changes under the pressure of semiotic diversity. It loses something of its old monopoly. Canonical images of writing as blocks of text in words - continuous, essay-like prose or the bound book with its linear sequence of chapters - are challenged and interrupted by a wider diversity of textual forms and genres bringing new combinations of verbal text/image or verbal text/image/sound. Writing finds itself in a more diverse landscape of textual communication, one that initially looks more fragmented. It enters more intense dialogues with other modes. It loses its smooth and continuist image in favour of something more seamed and interrupted.

Images of the well-formed - the well-formed sentence, the well-formed paragraph, the well-formed text - lose their former authority as fail-safe guarantors of communication in favour of more diverse and situated possibilities.

Writing does not move to the edge of culture in a world of image and the screen; but it does begin to look and feel different, taking on new material forms and new social roles as a mode among other modes rather than as a default form for communication and representation. The issue of what writing can do, and what it can't do, becomes an essential consideration in composing texts. At the same time, the existing potential of written text as a spatial as well as a temporal phenomenon becomes more pronounced and fertile.

Multimodality, Intermodality

So alongside multimodality it seems appropriate and necessary to talk about intermodality. Writing as a relational rather than a privileged mode, a semiotic contingent on moments and sites of communication rather than an expression of a universal logos. It is involved now in intermodal dialogues where before it had an unquestioned modal monopoly.

It is maybe not a matter of 'writing' being transformed wholesale as a mode; but of writing's resources being challenged and renewed in new conditions of production. For theory, this means less of a focus on the 'multi' and more on the 'inter'.

Writing and education

What might these new roles and images be for cultures traditionally steeped in writing and deference to writing, both a distinction and an islolation? I suggest that this rethinking has profound implications for education, where practices have long relied on writing - as an expressive resource and a tool for thinking, for sure, but also as a monitor of individual progress and as a device for testing and accreditation.

Writing has played a crucial role in the institition of education. Exams and tests assume that what a person writes down is somehow a sign of what they think, know or feel. Writing is used as evidence and display. It is supposed to record individual 'progress' and 'achievement'. It is treated as a transcript of thought. Writing, regulated by a hygienic system of correction and 'rules', is seen as a technology for both individualising and standardsing the acquisition - therefore the transmission - of knowledge. In examination rooms people write 'alone'; but they are being tested against eachother on the wager that writing equalises, makes it possible to compare like with like, smooths out the ragged work of social context and individual styles of knowing. The modal distinction, the separateness of writing, I suggest, owes a lot to this assumption that writing exerts a uniformity that de-contextualises and makes everyone appear to be 'equal'.

This is what you might call the glamour of writing as a mode; and also the distinction that makes writing so super-serviceable as a metaphor for productivity, for measuring learning, for sustaining a system of education. A multimodal perspective on texts and textual practice shakes up these practices of institution and challenges this glamour, especially gathered around the essay or 'essayist' writing, and the uses made of writing in what De Certeau (1984) calls 'the scriptural economy' of education.

The grounds of this economy change under a multimodal perspective. 'Student writing' is ideally reconceived as 'student textual production including writing'. Gatekeeping practices of examination and evaluation, which have traditionally used the mode of writing as the main (or only) technology to rank students by performance, and thus determine access to education's social capital (grades, awards, qualifications), suddenly appear less obviously effective, less stable and less convincing in such a shake-up of assumptions.

Writing as design

Writing does not disappear in a multimodal perspective, nor does it become marginalised; but it develops new modal functions, or expanded functions based on exisiting but formerly subordinate genres, in relation to other modes such as image. A good example is the caption, which could be seen as an 'intermodal' genre, newly suspended between image and word.

In this shift of modal authority and distribution, a change which is both a decentring and a renewal of writing as mode, the notion of design in student texts becomes central. And the opportunity spaces available for student production, often but not exclusively conditional on access to new technologies, become key sites of debate and struggle in curricular and disciplinary change.

No comments:

Post a Comment