Copy/paste has a poor press. It is usually seen as reductive, mindless, lazy - the textual equivalent of 'dumbing down'. It implies 'this is not your own work'. People talk about 'the copy/paste culture' to decry lack of originality - in writing, in music, in film.

Copy/paste has a poor press. It is usually seen as reductive, mindless, lazy - the textual equivalent of 'dumbing down'. It implies 'this is not your own work'. People talk about 'the copy/paste culture' to decry lack of originality - in writing, in music, in film.Except that, of course, everybody does it. And it has rapidly become part of the grammar of composition in our time. Copy/paste takes place all the time now in 'writing', but also has its equivalents in music and film, increasingly accessible to everyone with a computer or a mobile phone.

I am rethinking copy/paste. I see copy/paste as a citational activity. It's a form of quotation buried in the everyday.

Copy/paste appears to be a two-part process. I copy, I paste. But is it?

In Derrida's terms there are three, not two, parts to any citational move or 'borrowing': highlight, graft, extend.

Maybe Microsoft could make something out of that. I copy, I paste, I redirect?

Can anything be 100% copied? Don't we intervene all the time in what we 'copy'? If I 'copy' from one context and move the piece of text - however slight and humdrum it may be - to another context where I then 'paste' it - have I not also changed the original piece of text? It's now out of context, as all citation must be.

/Slash/

I copy/paste a lot but I no longer see it as a two-part function. The slash separating those two business-like verbs is where all the action is. It is a diverse middle-ground, potentially as subtle and context-sensitive as language itself.

As I use it, I am aware of copy/paste as a choice, with its own resources and limitations. It is not just about using another person's words and presenting them or re-using them as my 'own'. It is also a platform for response and commentary. It is a site for making new texts out of old ones, for borrowing and transformation. It is perhaps an example of what the French linguist Frederick Francois calls reprise-modification.

And it's also about efficiency, accuracy of re-presentation, saving time and energy.

Rather than teach a grammar of formulation, perhaps we should take a closer and more detailed look at copy/paste as a grammar of event and not structure, a grammar of intertextuality. It is one of those everyday sites that a focus on grammar as a logic of system, rather than a logic of event, will not allow us to see.

**************************************

Last week I did a workshop in a primary school on research skills. I was struck by how net-savvy the ten-year-old students were, how quickly they all recognised and used words related to the net and could talk easily about search engines, web sites and blogging. It's their world and they are entirely at home in it. And that includes copy/paste. Not as a passive or reductive operation but as a resource in a wider repertoire of movement between texts, of intertextuality.

However, the familiar problems which I noticed in observing children's online research three years ago - the overload of 'information', not knowing how to evaluate the usefulness of web sites, copying or highlighting chunks of text without knowing how to modify them or use them in a new way - these are clearly still problems in learning research skills in the world of the web. Teaching needs to address them in the context of the web search engine as much as the information book.

It was a fun workshop. Research can be a lot of fun. We made some progress by focusing on the need to have good research questions and on how to read, evaluate and exploit sources proactively, for specific purposes rather than passively storing masses of material.

But I left the workshop feeling, not for the first time, rather uneasy and swept out to sea. Once again that feeling that 'writing' and 'reading' are undergoing such revolutionary changes that cherished, schooled notions like 'write in your own words' are no longer useful.

We need to think of authorship in new ways, outside the rituals of education which insist on writing as a 'skill' that you can possess rather than a set of practices in which you can participate.

*************************************************

Where does academic writing begin?

I think these early engagements with 'information' in the primary school are the places where 'academic writing' begins.

Academic writing does not begin with being able to write per se. It begins with reading and writing together. Or, better, the practices which transfer language-as-read into language-as-written, and back again. I call these intertextual practices. I think they lurk in the undergrowth of all ecologies of literacy. They are often so ubiquitous that they seem invisible.

Quotation, paraphrase and referencing are mainfestly intertextual; but these are just the most explicitly marked and visible examples of a phenomenon dispersed through language and life. In them I would now include the much-maligned but nevertheless widely-used copy/paste.

Learning to write in academic and disciplinary ways is not just about essay-writing, formulation of sentences or 'argument'. It is about inhabiting and using other people's words, and knowing how to transform the weight of the already-written into new writing, borrowed words into 'my own words'. It is about acting intertextually. Style arises in the intertextual, not purely in the expressive.

As research activity moves more and more to the web and away from print sources - and for the ten-year-olds in my workshop most research will be predominantly web-based - the operations of reading and writing become so closely connected that at some moments they almost seem like one.

In fact, watching people use the web in public places like libraries, it is amazing how much writing is going on as part of reading, how much text is being created as it is consumed, how deftly keyboards and scroll bars and menus are being used to manipulate text and not just 'read' it.

The textul environments of the web invite multiple reading pathways; but they also invite writing - as response, annotation, feedback, creation. Using web text is rarely just about reading as we traditionally conceive it - decoding, absorbing, receiving meaning - but something increasingly more dynamic and interactive. We read, but we also get involved physically in what we read. We copy, translate, edit, annotate, respond.

Walter Benjamin's prediction about the rise of the mass media:

At any moment the reader is ready to turn into a writer

has come vividly true with the web.

In order to teach web research we need to see reading and writing not only as connected skills, but also as acts of design. As I read a text, I also re-make it. I don't just record 'information'. I transform it.

Copy/paste is part of the design vocabulary of text-making. It is widespread and diverse, though still curiously frowned on.

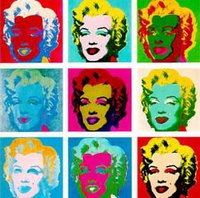

Rather than see it as a reduction of text, I would like to see it as a sign of diversity and change.

No comments:

Post a Comment